https://ko-fi.com/noahs_savior

Disclaimer: Most of the information about the history of joshi wrestling is only available in Japanese, I only have a beginner’s understanding of Japanese and have used the help of machine translations for some information I’ve gathered through the last couple of years of learning about this time period in wrestling. What I’ve found that’s been professionally translated is from the 2000 Japanese book Joshipuroresu Minzokushi by Kamei Yoshie, summarized in Keiko Aiba’s English-language book Transformed Bodies and Gender: Experiences of Women Pro Wrestlers in Japan. Other sources used for this was From the Stage to the Ring: The Early Years of Japanese Women’s Professional Wrestling by Tomoko Seto

The 1940s – Comical and Sexy Origins

Most discussion about the history of early joshi wrestling found in English usually start around the hysteria surrounding megastars, Crush Gals and Beauty Pair, few will talk about the importance of Mach Fumiake joining AJW in the early 1970s and almost single-handedly changing the Japanese public’s perception on what joshi wrestling was, and there are scant sources on what promotions and who their wrestlers were from the decades before AJW was created in 1968. The world of joshi wrestling before Mildred Burke’s tour in 1954 lived in an awkward space that had to deal with the aftermath of World War II and the new world of US/Japanese relations and slowly changing gender norms regarding work and American occupying forces’ talk of “women’s liberation.” Public rejection, and for some disdain, of joshi wrestling had much to do with how Japanese people -men especially- had to adapt to a world in which they hold lost their power from the destroyed empire and that they were now an ally to a larger and more malicious force that was just their enemy that had killed thousands upon thousands of Japanese citizens. As discussed in the episode about girls’ culture and the visual history of shoujo manga, the War had greatly devastated Japan in ways unseen by the world beforehand and many were left dead or stuck trying to figure out a new life in an unrecognizable Japan. Thousands lost any meaningful income through the death of male relatives and the physical destruction of the country, people had to figure out a way to just survive and cope with their current reality. The occupying US military forces had set out to make an example out of Japan and with the newly drafted constitution it aimed to model Japan after itself, media that was seen to promote old pre-war Japanese values were banned; Japan wasn’t being westernized in order to compete with and be equal to the West but it was now being forced to become Western because their traditional way of life was seen as antiquated and inferior to America’s. In this new world many found regular work by becoming entertainers for American soldiers on military bases and in clubs popular with the near 200,000 soldiers living in Japan during the postwar era up to the end of major military action in the Korean Peninsula in 1953. Women were not an uncommon sight as a part of entertainment being provided to occupying forces in both official capacity on-base and in unofficial means, usually as sex workers. This image of young, destitute Japanese women selling their bodies for the pleasure of the foreign invader would leave long-term effects ranging from bullying and ostracizing of biracial kids born from absent American GI fathers to the reaction relevant to the topic of discussion: the assumed erotic entertainment of women’s wrestling being performed for mostly American audiences on military bases and clubs made the general public distrust promoter’s intentions and the morality of the wrestlers themselves.

A trio of siblings left their current traveling theater company and formed their own group that got licensed to perform on US Army bases in 1946, as means to help care for their ailing father whose construction company had closed due to his illness. Pan, Shopan, and Lily (she doesn’t start to be billed by her birth name, Sadako, until 1953) create the Pan Sports Show as an act that includes a boxing match between Lily and Shopan with Pan acting as referee while a jazz band performs. Near the end of their thirty-minute time slot Lily and Shopan would throw off their gloves and start to wrestle each other, often ending with Lily stomping Shopan or Pan to cheers of the audience. For the next couple of years, the Pan Sports Show would continue to perform for majority American audiences on military bases and along the way would hire former contortionist, Tayama ‘Rose’ Katsumi, Tayama began her acrobat career in the 1930s and later became a saxophonist playing for American soldiers alongside her trumpeter husband until his death in the late 1940s. For many social critics and wrestling fans, the image of women wrestling in intergender matches was inherently erotic and with thousands of foreign soldiers with disposable income, many club owners with a large GI audience caught wind of the success of the Pan Sports Show and started advertising sexy women’s wrestling at their establishments. As mentioned in the previous paragraph, with the devastation caused by war, a lot of women sought licenses to perform at military facilities as they had the most money to offer but when that didn’t work out some women took to sex work —many panpan girls would look for American clients as they had more money than other Allied Forces soldiers and much more than the Japanese clientele—. The image of an American man interacting with Japanese women became associated almost exclusively with the idea that the women were offering sexual services in exchange for money; this predisposition along with the growing number of clubs advertising women’s wrestling helped create a perfect storm leading to the arrest of Lily and Pan on October 12, 1950. During a Pan Sports Show at a strip club, police came to stop the show and arrest its participants, the reason being that a man and woman wearing swimsuits and fighting was obscene. After spending the night in jail Lily and Pan were able to convince the police that they were actually siblings, they were released, and newspaper coverage of their arrest helped drum up interest and brought more people to their next series of shows.

The 1950s – Legitimacy, International tours, and Moral Panic

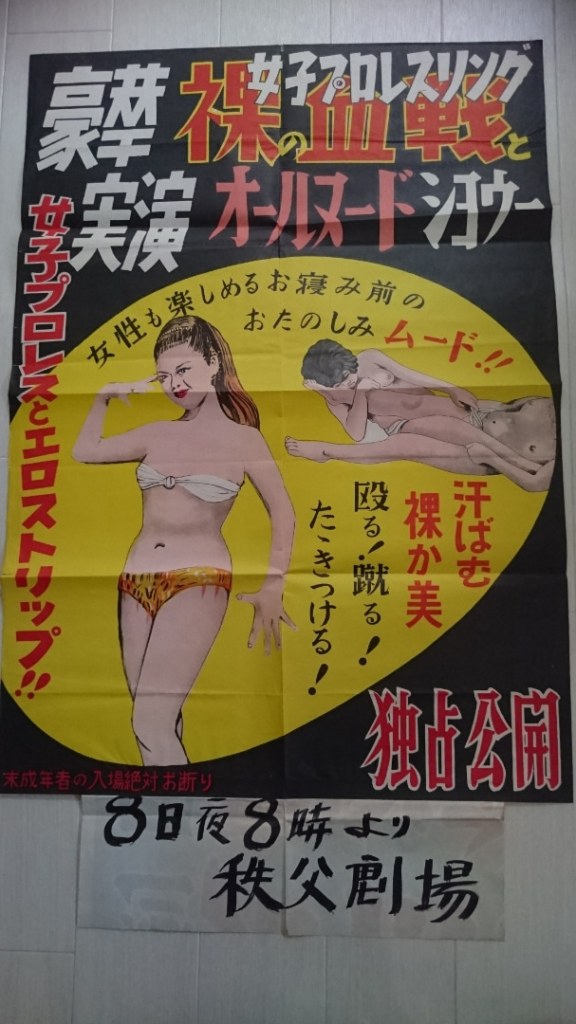

By 1951 the Pan Sports Show was renamed to the Pan Show and had a roster of four women that would wrestle in garter belt matches along with comedy skits and music. A year earlier the company had expanded beyond military bases and started to tour different strip clubs and nightclubs with more Japanese audiences, but this expansion into the domestic market meant that local papers began to report on this new brand of entertainment and with that brought the sexualization of the talent. Through the early 1950s multiple entertainment newspapers would run articles about this new type of show and even articles written in good faith still put an expectation of eroticism on joshi wrestling; one such article from an April 1950 edition of Sunday Movie talked about the motivation of Lily, Pan, and Shopan wanting to earn money to support their parents and the multiple skills that Lily possessed, but the article headline used the word nyotai (女体) which was the word of choice when talking about strippers. The same article that seemingly praised Lily and her brothers shared a page that talked about strippers at a different venue and this juxtaposition perfectly illustrated the common mindset from the mass populace during the mid-century, that even if the women wrestling never intended to be valued as just sexual bodies, many felt that the act of exposing skin and staging fake fights with men and other women for mostly foreign and male audiences at venues such as strip clubs was inherently at the same level as strippers and exotic dancers. Writers would either voice their disappointment in some promotions not having nearly enough eroticism present during matches or some would be amazed that the women were taking their matches seriously and were shocked that they also practiced and trained like athletes.

1952 was a big year for the Igaris and the Pan Show wrestlers when a fan of Pan and Shopan, Fujii Shigetoshi, introduced them to an American friend of his, Elmer Hawkins. Elmer Hawkins was a technical sergeant stationed at Tachikawa Air Base who had a background in amatuer wrestling, Hawkins eventually offered to train the Pan Show wrestlers and he and Shigetoshi paid for a full renovation of the gym at the Igari house in Tokyo. During the gym renovations Lily told her brothers that she doesn’t want to wrestle at US military bases anymore and that her and the other women wanted to become true professional wrestlers, while their home gym was being worked on Lily starts training with the Waseda University men’s team with permission from their coach, Ichirou Hatta. This shift from an entertainment show to a bonafide wrestling promotion saw the creation of the All Japan Women’s Wrestling Club (全日本女子レスリング倶楽部) in 1952 featuring Lily Igari, Katsumi Tayama, Hiroi Houjouji, Yumi Katori, and former sumo wrestler Yasuko Tomoe. With the Women’s Wrestling Club Pan Igari said, “We will make every effort to avoid making our women’s wrestling a plaything for lecherous men [unlike women’s sumo]” quote from Tomoko Seto’s journal. Those efforts included no longer appearing in venues like nightclubs or military bases and focusing on proper training for the women, when the gym renovation was complete training was led by Hawkins, other American servicemen, and Japanese practitioners of Judo and karate including the legendary judoka, Masahiko Kimura. Shopan believed that their style of wrestling should be like American wrestling and still be entertaining for the audience because if you have nothing to bring the crowds back then all your wrestling skill would be for naught.

A new entertainment medium, broadcast television, started to gain traction in 1953 and would become an integral part of creating the legend of Rikidozan when he and Masahiko Kimura faced the Sharpe Brothers on February 19, 1954. Televisions were not an affordable appliance for Japanese families in the early post-war era so many public areas would install televisions for crowd A new entertainment medium, broadcast television, started to gain traction in 1953 and would become an integral part of creating the legend of Rikidozan when he and Masahiko Kimura faced the Sharpe Brothers on February 19, 1954. Televisions were not an affordable appliance for Japanese families in the early post-war era so many public areas would install televisions for crowd viewing, playing early NHK broadcasts and the new and growing sport of puroresu. Closed circuit broadcasts of Rikidozan matches made it so that many people across Japan could watch this new hero and his allies defeat the evil foreigners, the growing popularity of Rikidozan’s JWA promotion would trickle down to women’s wrestling as more joshi promotions started to form during the early mid-1950s. In March 1954 a new promotion, All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association (全日本女子プロレス協会), held their first auditions and created their inaugural roster that included Yuriko Amami: wife of the eldest Matsunaga Brother. Later that year in November, one of the most important events in the history of Japanese women’s wrestling began, the week-long Japanese tour by Mildrude Burke’s World Women’s Wrestling Association (WWWA). Burke, May Young, Ruth Boatcallie, Gloria Baranttini, Mildred Anderson, and Rita Martinez held a series of wrestling shows throughout Tokyo and featured Japanese women in the opening matches. The Americans’ tour was covered by the sporting and mainstream press and one of the tour stops was even broadcast on television, journalists were amazed at the women’s strength in-ring and their feminine beauty out of the ring. With the novelty of foreign women wrestling and the still-growing popularity of Rikidozan, the WWWA tour was a hit with the larger masses and led many young women to begin training to become wrestlers themselves. All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association held their second and third auditions in January and March of 1955, the second class included sisters, Reiko Yoshiba (birth name Reiko Matsunaga) and the younger Yoko Yamaguchi (birth name Yoko Matsunaga). By the middle of 1955 there were eight different women’s wrestling promotions and an estimated 200 women wrestlers, including strippers who would wrestle in clubs, and in September the Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Federation (日本女子プロレスリング連盟) formed with the goal of organizing these new promotions and finding a way to legitimize the sport of women’s wrestling in the eyes of the Japanese public. The Japan Women’s Wrestling Federation made its biggest impact on joshi wrestling on the days of September 10 and 11 with a two day tournament featuring singles and tag matches set up to crown inaugural champions in various weight classes — Flyweight (Ritsuko Yoshikawa), Bantamweight (Yoko Tachibana), Featherweight (Kiyo Obata, younger sister of Chiyo), lightweight (Tomoko Kubo), Middleweight (Fujiko Azuma), light heavyweight (Yoshiko Yamamoto), lightweight tag (Sadako Igari & Katsumi Tayama), and middleweight tag (Yoshimi Toyota & Noriko Oi)—. Even with the stardom of Rikidozan and the success of Burke’s WWWA Japanese tour, domestic women’s wrestling can’t continue its momentum and the Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Federation folded in 1957 due to multiple promotions facing serious slumps in profit and many also closed their doors in the last years of the decade.

We will make every effort to avoid making our women’s wrestling a plaything for lecherous men [unlike women’s sumo]

Pan Igari (quote from “From the Stage to the Ring” by Tomoko Seto

Since the sport’s beginning as comedic entertainment performed at American military bases and clubs frequented primarily by men and American GIs there had been discourse by social critics and concerned citizens about the motivations of promoters and what exactly about women wrestling attracted an audience in the first place. In the early days in the late 1940s many voices —especially that of Japanese men forced to adapt to a new life in a Japan under occupation by its former enemy, now turned ally, and being molded in its image in order to combat the rise of communism in the Asian Pacific— had a negative reaction to the image of young Japanese women performing for an audience of foreign men, add in that at this time it was still common for strip clubs to have dancers perform wrestling matches as a part of stage shows and even host legitimate promotions as special in-house entertainment . A common theme throughout newspaper reporting during the 1950s were male writers being either surprised at the lack of actual eroticism and the display of wrestling ability at these shows, or they assumed that the act of women wrestling in both intergender, and single-sex matches was deviant and should not be in view of the general public. By this time pro wrestling centric magazines had occasional coverage of women’s shows and discussed the wrestlers and matches in earnest while also making sure to emphasize the women’s morality and motivations for joining the sport, in contrast to how mainstream publications often reported on popular women’s wrestling in the same manner as strippers and other erotic entertainers. A Central Review report by Hidezo Kondo said that the wrestlers of the Women’s Wrestling Club were inferior to Rikidozan’s promotion and, “…it’s lack of erotic taste, far inferior to striptease.” Much like how Kobayashi Ichizou spent years making a concerted effort to convince audiences that the early ‘Zuka Gals’ were honest young women with good morals, Women’s Wrestling Club and Tokyo/Toyo Joshi Pro Wrestling made conscious decisions to do what they could to distance themselves from the reputation of strip club side shows or yakuza-run fake promotions. Both promotions had stopped holding shows at clubs in favor of public gyms and theaters by 1955 and Tokyo/Toyo Joshi Pro Wrestling created three strict rules for each of their wrestlers to follow: no smoking, no drinking, and no dating.

The 1960s – CrazySexyCool

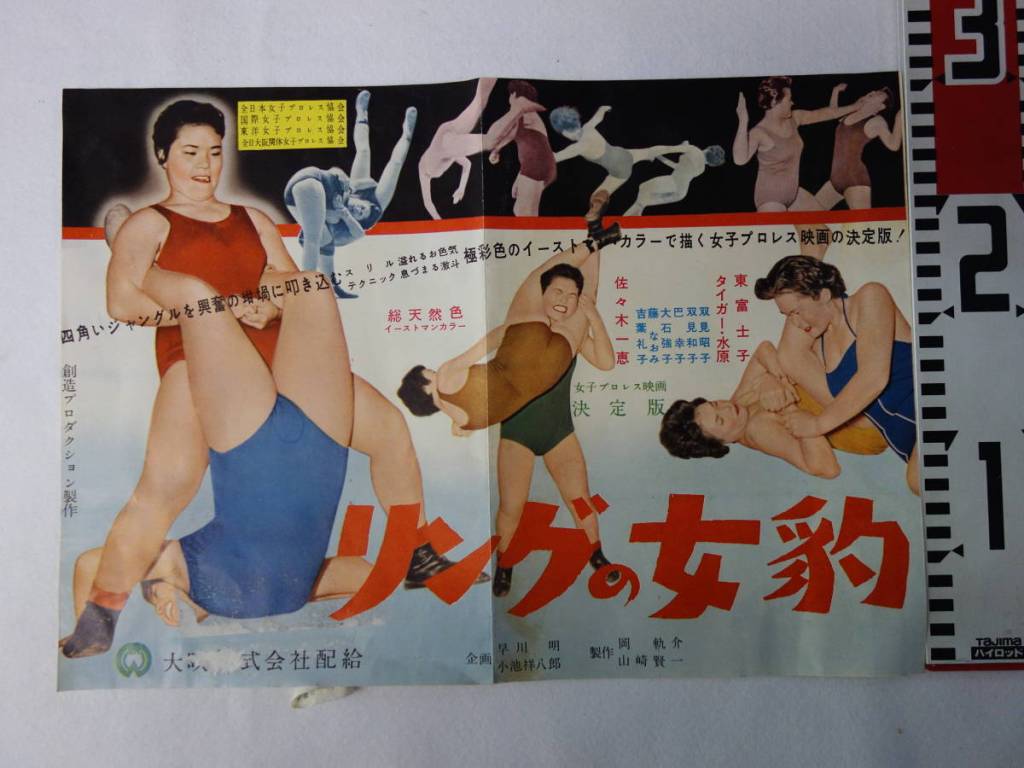

Despite the continually growing popularity of men’s wrestling and women’s wrestling shows headlined by American women drawing audiences, the public at large didn’t want to associate with Japanese women’s wrestling. Multiple promotions tried to distance themselves from the world of strip clubs in various ways but the struggle of convincing people outside of the wrestling bubble that joshi wrestling wasn’t obscene entertainment proved to be near impossible for the next ten years. A short 24-minute documentary released in September 1957, (リングの女豹/Lady Leopards of the Ring), showcased wrestlers from the young All Japan Women’s Wrestling Association (including future NWA Women’s World Champion, Yukiko Tomoe) but by then interest had waned from the WWWA tour three years prior, some wrestlers had to become freelance and picked up part-time work just to support themselves. On April 19, 1967, Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association (日本女子プロレス協会) was formed by members of the former All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association and many freelance wrestlers in another effort to make the greater public view joshi wrestling as a sport and not as “a child of pro wrestling and stripteases.” Ten days later an event was held, the Japan Championship Series, by the new promotion headed by Touichi Mannen, Takashi Matsunaga, and Morie Nakamura. Business wasn’t immediately successful and the new promotion’s training facility were just mats lining a parking lot outside a building in Chiyoda Ward and tragedy soon struck on July 29 when a trainee died from a head injury suffered from hitting the back of her head on the uncovered asphalt, Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association would catch their first real break the following year when they created a working relationship with the NWA and women’s world champion, Fabulous Moolah, and a Japanese tour featuring the champion and other women was set up for March of 1968. The joint shows were called the World Championship Series and featured multiple NWA Women’s World Championship title matches between Fabulous Moolah and Yukiko Tomoe, Yukiko debuted in All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association in 1955 and featured in the 1957 documentary and matched the height of the tall American women, —Yukiko was billed at 170cm while Moolah was billed at 168cm, both tall heights for women born before the mid-century— and wrestled a two-out-of-three falls match to a 60-minute time limit draw on March 2 at Taito Ward Gymnasium. Days later at Higashi Osaka City Gymnasium Yukiko Tomoe would defeat Fabulous via a count-out 4 minutes 53 seconds into the third fall and become the first Japanese woman to hold a NWA championship, but Yukiko would get two defenses before dropping the title back to Moolah on April 2 at Hamamatsu City Gymnasium.

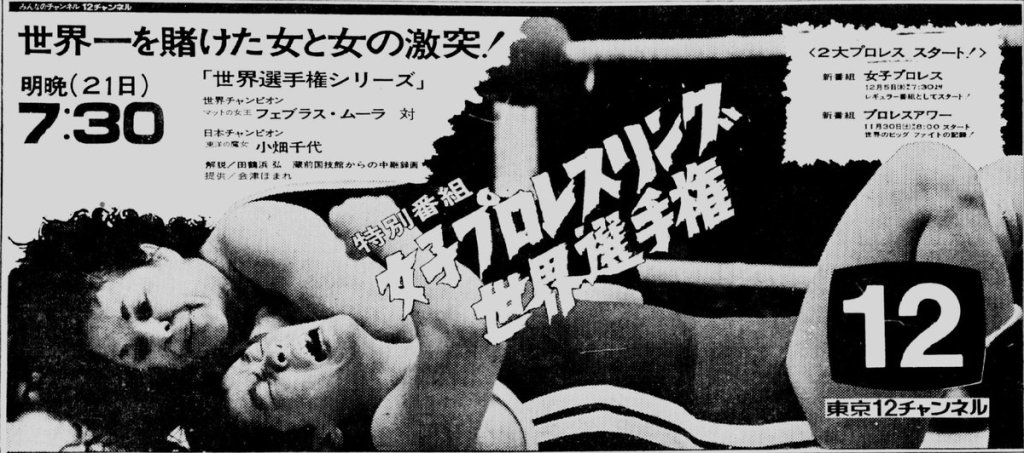

A mere two months later everything in the world of joshi wrestling was about to shift, after months of in-fighting Takashi Matsunaga, Touchi Mannen, and most of the wrestlers leave to create a new A mere two months later everything in the world of joshi wrestling was about to shift, after months of in-fighting Takashi Matsunaga, Touchi Mannen, and most of the wrestlers left to create a new promotion, All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling (全日本女子プロレス), with Mannen serving as its first president. The exodus left Nakamura as the president of Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association, which still carried an advantage over the new AJW for the little time they had left, a working relationship with Fabulous Moolah. When the split happened, allegiances were based mostly on Takashi Matsunaga grabbing family members to join him in making their own promotion, the second major attempt at a new joshi wrestling promotion in a single year’s time. It wasn’t easy for AJW in the beginning as unknown voices were spreading rumors that they were associated with the yakuza and they were stuck having to rent out the same strip theaters that Takashi and his former business partner were determined to leave behind in their short-lived partnership, meanwhile Nakamura and his new ace, veteran Chiyo Obata, were about to make the first major step in making domestic women’s wrestling popular when Fabulous Moolah returned to Japan in November with the International Women’s Wrestling Association title. Chiyo Obata would challenge for the IWWA title and the two would wrestle on November 6 with cameras from Tokyo Channel 12 (now known as TV Tokyo) filming for an upcoming special broadcast, “Women’s Wrestling World Championship Fabulous Moolah vs Chiyo Obata” aired on Thursday November 21, 1968, at 7:30pm to an outstanding rating of 22.4%. That was the highest viewing audience at that point for Tokyo Channel 12 and the main sponsor for the special show, Santen Pharmaceutical, was so pleased with the numbers that they approached Tokyo Channel 12 to produce regular programing featuring Obata and the wrestlers of the Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling Association. The new show was called, “Women’s Wrestling Broadcast World Championship Series 女子プロレス中継 世界選手権シリーズ” and began airing on December 5 in the primetime slot of 7:30 pm-8:00 pm with focus on Obata and others wrestling foreigners while defending the IWWA singles and tag team championships. This was the first regular broadcast of joshi wrestling and it continues to draw good ratings in the major regions of Kansai and Kanto, keeping the main sponsor and executives at Tokyo Channel 12 happy with having joshi wrestling on the airwaves. The Championship Series performs well enough that AJW was given two trial broadcasts on May 8 and May 29, 1969, but the ratings didn’t meet expectations and AJW was unable to get a television deal.

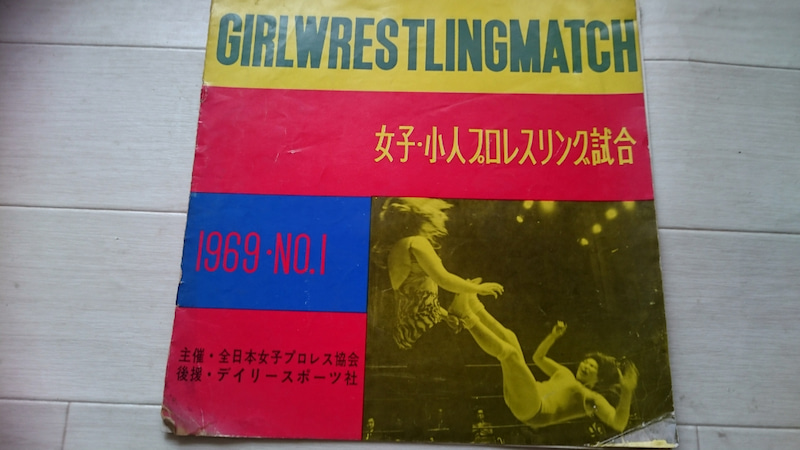

When AJW was created in June of 1968 many of its members were a part of the large Matsunaga family, making it the second family-run wrestling promotion after Pan, Chopin, and Sadako created When AJW was created in June of 1968 many of its members were a part of the large Matsunaga family, making it the second family-run wrestling promotion after Pan, Chopin, and Sadako created the All Japan Women’s Wrestling Club in 1952. The Matsunaga’s involvement in joshi wrestling started when the two Matsunaga daughters, Reiko and Yoko, joined the All Japan Women’s Wrestling Association a year after their sister-in-law, Yuriko Amami. When the two sisters started wrestling, Takashi is brought in to help train the wrestlers due to his background in judo and in a couple of years three of the other brothers get involved in the daily operations of All Japan Women’s Wrestling Association. The eldest Matsunaga brother isn’t directly involved in the world of wrestling, but his wife was Yuriko Amami, and his eldest son married pioneering idol wrestler, Mimi Hagiwara, in 1980. Jumbo Miyamoto and Kyoko Okada are cousins to the Matsunaga siblings and the niece of the second-eldest Matsunaga was wrestler Aiko Kyo, who debuted in 1965. The original Mariko Akagi was married to the fourth Matsunaga brother and a later wrestler who would become the second woman to wrestle under the ring name Mariko Akagi, Touko Kaseya, was a distant relative of the Matsunaga family. Eleven women and four midget wrestlers from Japan Women’s Wrestling Association jumped ship to the new promotion and the debut show in Shinigawa also featured Americans, Lucille Dupre and Mary-Jane Mull, from the American Girls’ Wrestling Association (AWGA). As previously mentioned, rumors started early that there was a yakuza connection with the Matsunaga family so many venues closed their doors and left AJW with having shows outdoors or even occasionally renting out a strip club. Shinji Ueda, then editorial director of Daily Sports and the inaugural WWWA commissioner, was a supporter of AJW since the first show and brought regular coverage of the entire sport of joshi wrestling not seen since the first boom of popularity over a decade prior. The Daily Sports relationship helped bring some respectability to the new promotion in its infancy, but it wouldn’t begin to gain an identity until the early 1970s when AJW got the rights to the WWWA name and associated titles and landed its first megastar, Mach Fumiake.

The early history of joshi wrestling is one that is caught in the crosshairs of a rapidly changing Japan, a society destroyed physically and financially, rebuilding itself with the strong arm of America into a country that would again become a socially conservative and stable economy for the Asian-Pacific region during the mid-century. Japan after the war has to create a new identity and many aspects of personal and professional life were challenged by young people in the post-war era, female liberation as described by the American occupation forces versus Japanese feminists and conservative activists that were concerned about young people and families being exposed to vulgar content and “unhealthy entertainment”: in this context anything pornographic that could disturb the stability of the ideal family through sexual temptation. Women were forced into the workforce either by death or disability affecting male relatives in the immediate post-war and many found the best pay entertaining American soldiers thanks to their now impoverished conditions. No sympathy was shown towards female sex workers in the decades after the war and due to their literal proximity, joshi wrestling dealt with similar opprobrium that faced strippers and club dancers until the early 1970s, creating a dearth of information on the sport and unflattering coverage by mainstream outlets until the debut of Mach Fumiake in 1974. Many of the earliest joshi wrestlers joined the sport to support their parents and families and during the late 1950s as more wrestlers joined promotions the main motivation for becoming a wrestler was that it was a way to support themselves and earn money. Was the Edo-era classist thought that young unmarried women traveling for work in manual labor was symptomatic of girls growing up in poor families still creating an unconscious bias against young women that were participating in the new and unknown world of women’s wrestling? Multiple writers throughout the 1950s scratched their heads as to why people would go to see women wrestle, were the audiences genuinely interested in seeing women participate in predetermined fights or was this another case of men taking advantage of women and catering to a debauched audience looking for another source of erotic entertainment? The New Life campaigns of the 1950s focused on housewives and their roles as the caretaker of the household and supporting her husband as the family leader and provider, her increased importance to companies and marketing teams meant that her opinion and favor carried increased weight —the cancellation and the purgatory of midnight air times faced by early joshi wrestling shows on broadcast television were results of call-ins from concerned viewers, cited to often be at-home mothers and housewives—. Joshi wrestling is a direct result of the collapse of an empire and the nation that formed in its shadow but unlike their male counterparts, women in wrestling weren’t allowed to be heroes, time and time again they and their promoters had to prove that they were morally upstanding women that most often just wanted to be able to independently support themselves. The traditional social structure of Japan meant that male authority figures had to be public faces of these new joshi wrestling companies to show the public that a real leader was making sure that the young women were living honest lives and had discipline, the infamous three taboos created by Tokyo/Toyo Joshi Pro Wrestling would be later adopted by AJW with the added caveat of a retirement age of 26 to continue to promote that the women wrestling weren’t living deviant lives. A “healthy image” wouldn’t become associated with joshi wrestling until the elements of pre-war girls’ culture and post-war shoujo manga would perfectly align to create a cultural zeitgeist in the early 1970s and joshi wrestling sees their first megastars, Mach Fumiake and Beauty Pair.